“A Savage Art: The Life & Cartoons of Pat Oliphant” is a riveting portrait of a savage pen, a dying media ecosystem, and art as resistance.

No time to read? Click the button below to listen to this post.

MORBID MINI: A Savage Art isn’t just a documentary about a cranky genius with a pen; it’s a eulogy for a world where savage cartoons could still make presidents sweat. In an era of “fake news,” corporate caution, and creeping fascism, this portrait of Pat Oliphant doubles as a warning shot: when we silence the artists and the journalists, the real horror story begins.

There’s a scene that never appears in A Savage Art: The Life & Cartoons of Pat Oliphant, but you can feel it between the frames: a president, any president, unfolding a newspaper at breakfast and going pale when he hits the editorial page. One drawing. One caption. One vicious little penguin in the corner. And suddenly the most powerful man in the world has to sit there and stare at the way someone else sees him.

Bill Banowsky’s documentary is, on its surface, a calm and respectful biography of one of the most influential political cartoonists of the last century. Underneath, it plays like a love letter to a disappearing weapon—and a warning about what happens to a country when it decides it no longer needs people who make presidents and people in power flinch.

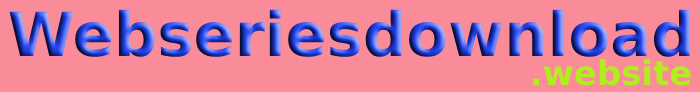

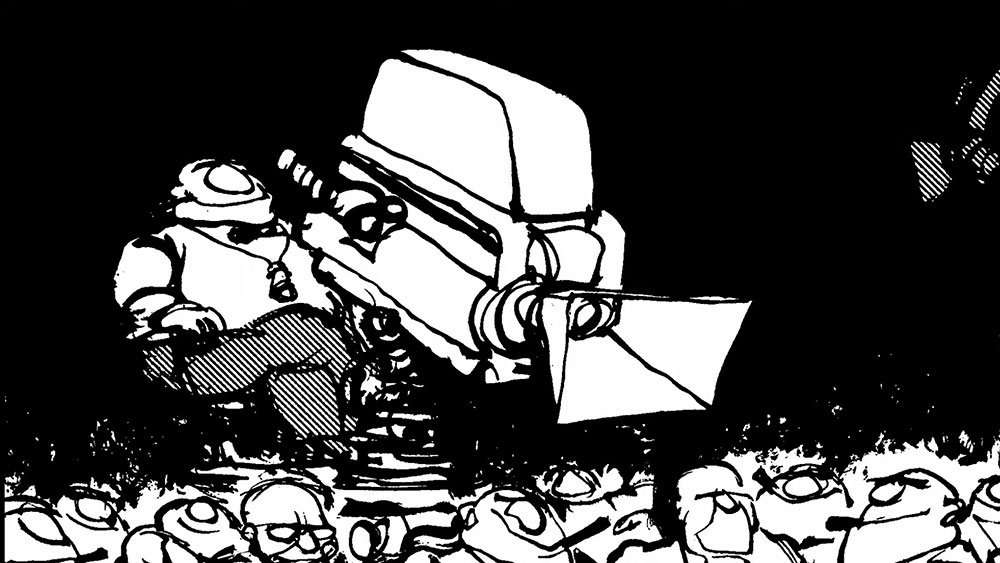

The film traces Oliphant’s journey from a young artist in an Australian newsroom to a defining voice in American political life. Over more than half a century, and across ten U.S. presidents, he turned daily headlines into images that cut straight through spin and talking points.

Instead of “analysis,” he gave us a razor in the shape of a pen.

Banowsky builds the portrait from layered elements: family members recalling the man behind the acid wit; colleagues discussing his work ethic and stubborn streak; archival footage of Oliphant himself, droll and quietly furious; and, most importantly, a flood of cartoons. Hundreds of them, animated just enough to feel alive, but never so much that the line loses its bite.

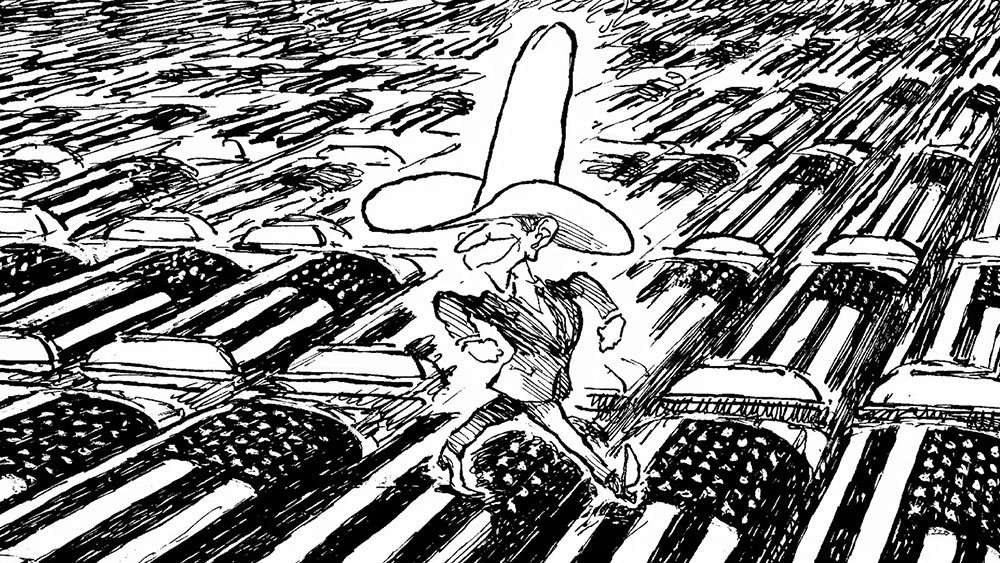

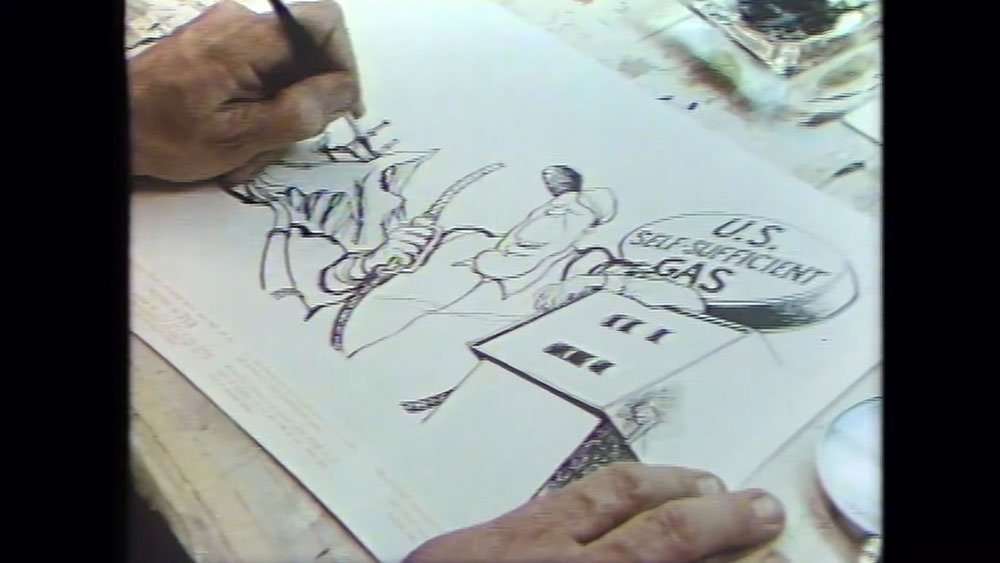

We see how a typical Oliphant cartoon comes together, turning a statesman into a sulking bully or an emperor with no clothes.

The film also spends time with his process, emphasizing the sheer grind of it. Three cartoons a week sounds modest until you remember each one has to be timely, legible, morally pointed, funny, and worth risking hate mail and death threats over.

Oliphant, for his part, treats backlash as a performance review.

If the powerful were offended, it meant he’d hit the right nerve. “You’ve got to wake up every day angry,” he is quoted as saying. It’s a mantra that sounds half like advice to young artists and half like a survival strategy in a country that prefers its criticism softened and safe.

Visually and structurally, A Savage Art is straightforward: talking heads, archival clips, and an orderly march from early years to legacy. It’s not formally radical, but it doesn’t need to be.

The radical thing is in the images themselves, and the movie is smart enough to get out of their way.

What makes the documentary feel urgent instead of purely nostalgic is the way it situates Oliphant’s career against the slow collapse of the ecosystem that sustained him.

Again and again, we hear about the shrinking number of full-time staff cartoonists, the hollowing out of local newspapers, and the creeping timidity of editors who would rather run something “inoffensive” than risk a complaint call or an advertiser tantrum.

In a time when the United States has slid to 57th place on the World Press Freedom Index, the space for dissent is shrinking.

Then there’s the internet, which the documentary treats as both a blessing and a curse. A single image can now reach millions of people in an afternoon. A cartoon no longer has to wait for the morning edition to make its point. But virality doesn’t necessarily translate into food or rent.

Artists watch their work pinball across timelines stripped of signatures and context, morphing into memes that carry their ideas but not their names.

In this new attention economy, outrage travels fast while authorship evaporates.

Memes and low-effort “gotcha” graphics increasingly take the place of crafted political cartoons. The work of turning complex issues into a single sharp, honest image—an image you might wrestle with for days—is devalued in favor of something that can be churned out in minutes and forgotten just as quickly.

A Savage Art quietly insists that the difference matters.

A real editorial cartoon isn’t just a punchline; it’s an argument. It condenses a moral stance into one unforgettable picture. It forces you, if only for a moment, to confront what you’d rather not see.

In the best hands, it can illuminate something no straight news story ever quite gets at.

To understand why that matters, the film reaches backward as well as inward. It gestures toward the long history of political cartooning—not as a cute side dish to “real” journalism, but as one of the oldest forms of public argument we have.

Long before cable news panels and quote-tweeted threads, you had a snake cut into pieces on a page: Benjamin Franklin’s “Join, or Die,” woodcut, urging the American colonies to band together. That image became a kind of founding meme, a reminder that the fate of the country rested on people seeing themselves as part of something larger than their individual interests.

Oliphant picks up that thread and yanks it through the second half of the twentieth century.

His work is steeped in history. The reason his cartoons land is because he knows exactly which ghosts to summon—what wars, what scandals, what cultural myths to reference—in order to make the present look as damning as it is.

The film underlines that this kind of work is not “neutral,” and it isn’t supposed to be. Political cartooning, at its best, is partisan on behalf of the public.

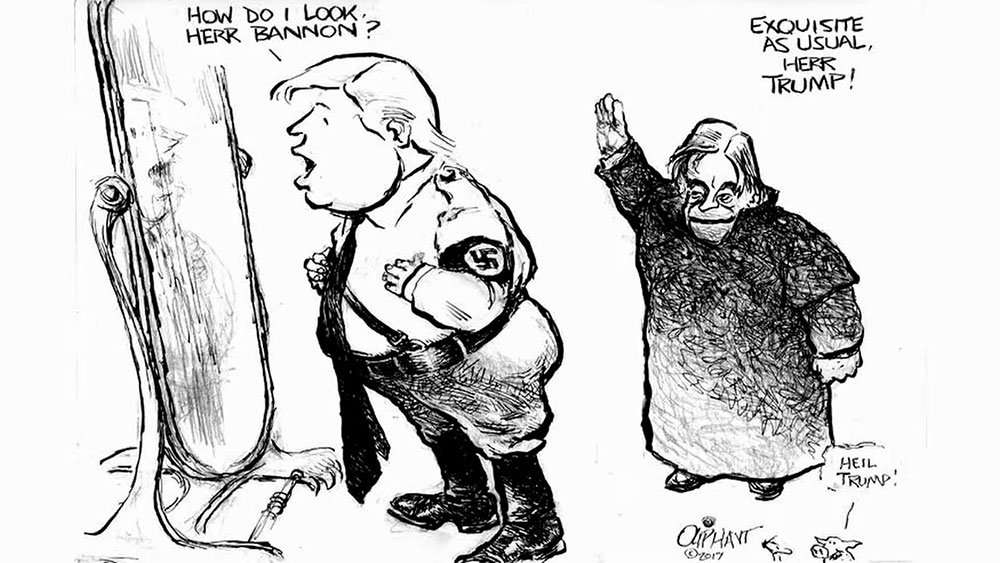

It takes sides against hypocrisy, cruelty, and authoritarian creep. It doesn’t ask if both sides feel equally flattered. If anything, Oliphant’s career is a case study in refusing to smooth over his anger for the sake of being palatable.

That makes his story feel especially pointed in a moment when presidents label the press “the enemy of the people,” wave away any story they dislike as “fake news,” and treat journalists and satirists as saboteurs rather than watchdogs.

In a world like that, every sharp cartoon becomes a tiny act of defiance: a reminder that there are still stories about power the powerful don’t get to write.

Political cartoons and horror movies are cousins; both rely on compression.

Both transform abstract systems—racism, fascism, imperialism, corporate greed—into something you can’t pretend you didn’t see.

A single panel of a smirking president using the Constitution as toilet paper. A single frame of a masked killer moving through a world that shrugs at the bodies piling up. Different media, same gut punch.

Horror has always thrived in the cracks where polite discourse fails. When governments insist everything is fine, horror comes along with plague zombies, home invasions, and masked purges to say, “Actually, it’s not.” It sneaks in anxieties about censorship, surveillance, and state violence under the guise of entertainment. It makes fear visible.

Oliphant’s work does something similar with humor. His cartoons are often funny, but they’re rarely just funny.

The joke is the pulling of the rug. The image underneath is the real point. It’s the realization that the monster isn’t supernatural; it’s elected. It’s wearing a suit. It’s signing laws. It’s smiling for the cameras.

When a culture starts to clamp down on dissent—whether through laws, economic pressure, or an endless chorus screaming that any criticism is unpatriotic—it doesn’t just hit journalists. It hits everyone whose job is to hold up a mirror. That includes satirists, cartoonists, activists, and yes, horror filmmakers.

The more “dangerous” art feels, the more necessary it probably is.

For all its affection for its subject, A Savage Art doesn’t end in a place of comfort.

By the time the credits roll, Oliphant has retired. Newspapers have withered. The space where someone like him could thrive has narrowed to a sliver.

Oliphant spent more than sixty years choosing to provoke rather than reassure, to swing at targets everyone else tiptoed around, to keep drawing even when it made his life harder. He didn’t care what the political establishment wanted from him. He cared whether his work told the truth as he saw it.

In an age of AI-generated “art,” automated content farms, and endless doomscrolling, that kind of labor-intensive, deeply human provocation feels almost radical.

A Savage Art makes the case that we still need it—that there is power in a handmade image that took time, anger, and thought to create. There is power in something that doesn’t just flatter your existing beliefs but unsettles them.

Because the alternative is a dangerous quiet. A media world where nobody risks offending anyone important. A news cycle that treats every outrage as just another tile on a screen. A culture where satire is flattened into low-effort dunking and serious reporting is dismissed on sight as “fake.”

A Savage Art doesn’t scream its message. It doesn’t have to. It simply shows us a man who woke up angry, picked up a pen, and refused to stop drawing monsters with human faces.

The question it leaves hanging—and the question horror fans, journalists, and artists of all kinds should be asking—is simple:

When the people who do that work are gone, who benefits from the silence?

Overall Rating (Out of 5 Butterflies): 4