“He Kills at Night” is a bleak, claustrophobic holiday horror that forgoes all cheer for a twisty, claustrophobic cat-and-mouse thriller.

No time to read? Click the button below to listen to this post.

MORBID MINI: A battered woman, a blood-soaked stranger, and a snowbound Christmas Eve drive turn a single car into a rolling torture chamber. He Kills at Night trades holiday cheer for claustrophobic dread, gendered terror, and a finale that hits like black ice.

Holiday horror usually comes wrapped in a familiar package: killer Santas, demon toys, office-party bloodbaths. He Kills at Night wants nothing to do with any of that. Instead, writer James Pickering and director Thomas Pickering park us in the confines of a car on a collision course with destiny, letting the mounting tension slice like a knife while shredding any semblance of holiday cheer.

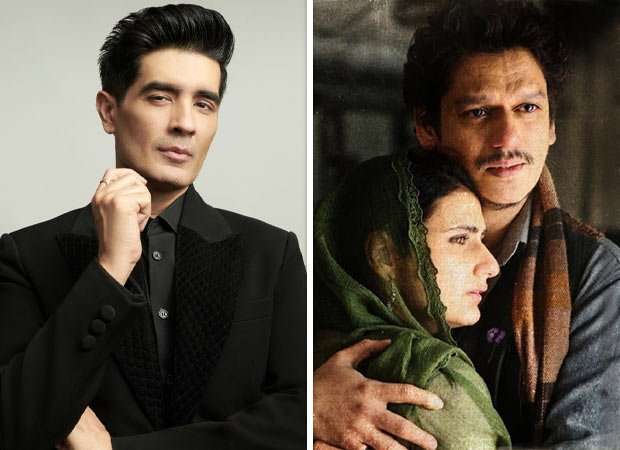

The setup is brutally simple. On a snow-choked English backroad, Marie (Levi Heaton) is driving home, bruised and shaken, desperate to reach her estranged family before the night is over. When she’s forced to stop for a car blocking the road, she stumbles into something far worse than a traffic hazard. A blood-streaked stranger, Alan (Richard Galloway), is waiting in the dark. He can’t drive. He needs to flee the country. And he’s more than willing to use violence to make Marie his getaway driver.

Most of the film unfolds within those four doors, the camera hovering between Marie’s haunted eyes and the shadowy silhouette behind her.

Alan rarely has to raise his voice; the power imbalance is already carved into the frame. Marie is literally boxed in between the steering wheel and the man who might be the serial killer the radio DJ keeps warning listeners about between cheery Christmas songs.

That radio is the film’s first stroke of cruelty.

Early on, a DJ invites callers to speculate about a string of missing women. Are the fears overblown, or is there really a predator out there?

It’s the kind of morbid holiday chatter that might be shrugged off as urban legend—until Marie hears it while trapped in a car with a stranger who refuses to let her stop, even for fuel, and dares her to ask whether he’s the monster everyone is whispering about.

Alan’s justification for the horror he inflicts is chilling in its simplicity. The world, he insists, is rotten to the core, and he’s just speeding up the decay. That fatalism feels uncomfortably familiar in a time when people explain away cruelty as inevitable. His nihilism becomes another weapon, chipping away at Marie’s sense that anyone is coming to save her—or that anyone even deserves saving.

The film keeps circling back to gendered violence, and it does so without reducing its women to easy victims. Before Marie’s ordeal truly begins, we see Alan attempt this same trick on another lone driver. She’s smart and scrappy, and she fights back with everything she has.

Her resistance is exhilarating, but the outcome is still horrifying in a way that underlines just how fragile “doing everything right” really is when you’re alone with a man who has already decided your life is negotiable.

Later, three flashbacks drop us into the lives of other women who have gone missing in recent months.

They’re snatched from spaces that feel safe and moments that should be mundane, even boring. We never see the whole aftermath. Instead, the film shows us just enough to let our brains fill in the worst-case scenario. Are they dead? Hidden somewhere? Is Alan responsible, or is something else happening? Those unanswered questions hang over every mile Marie drives.

All of this plays out against the relentless hush of falling snow and the forced cheer of Christmas decor glimpsed through windshields and farmhouse windows.

The Pickering brothers lean into the dissonance: familiar holiday standards drift over scenes of terror, and when the music drops out, a plaintive piano line takes over, echoing Marie’s grief and panic more than any big orchestral sting could. Christmas here isn’t cozy; it’s a magnifying glass.

The season’s insistence on togetherness and joy only amplifies Marie’s loneliness, her estrangement from her family, and the ugly reality that many people spend the holidays trapped in their own private hells—abuse, depression, unresolved trauma—while the world tells them to be grateful.

As the night wears on, the cat-and-mouse dynamic between Marie and Alan becomes the film’s true engine.

Heaton is a powerful anchor here. Her Marie is exhausted, traumatized, and terrified, but never passive. She’s constantly calculating—testing boundaries, prodding for information, letting just enough fear show to keep Alan’s ego fed without surrendering entirely.

Galloway’s Alan is a different challenge. He has to be frighteningly unpredictable without turning into pure camp, and for the most part, he nails it.

Without spoiling specifics, He Kills at Night refuses to arrive at the destination you’re probably mapping out in your head from the first act.

The final stretch lands with a nasty jolt that recontextualizes what we’ve been watching, and it does so without betraying Marie’s character or the film’s grim view of the world. It’s less a “gotcha” twist than a revelation that snaps everything into a more unsettling shape.

It’s also worth noting how much this film accomplishes on a modest budget. You can feel the influence of lean, mean road movies and early Carpenter in the pacing and score.

If you’re looking for campy festive horror to pair with spiked hot cocoa and ugly sweaters, He Kills at Night is not that movie. There are no winking one-liners, no killer Santas, no cathartic crowd-pleasing kills. Instead, it offers something colder and more lingering: a bleak, tightly wound survival story.

Full of gripping tension, it offers no comfort, only the icy chill of grim desperation.

Overall Rating (Out of 5 Butterflies): 3.5

He Kills at Night landed on VOD in the US and UK on December 2, 2025.